In Japan, craftsmanship isn’t driven by spectacle. It’s shaped by the rhythm of the hand, the season, and use. Whether forged in fire, carved in wood, or coaxed from water and bark, the tradition of crafting has never been separate from daily life. There is no line between what is beautiful and what is used. Which allows it to endure..

You feel this deeply at The Japan Folk Crafts Museum in Komaba, Tokyo. Established in 1936 by Soetsu Yanagi—a thinker shaped by Buddhist aesthetics and the British Arts and Crafts movement—the museum exists not as a monument to rare art but as a home for everyday beauty. Yanagi's belief in mingei—a term he coined meaning "folk craft"—, championed the artistry of anonymous makers: farmers, weavers, potters, and carpenters whose work quietly shaped daily life. Rather than celebrating the famous or the elite, mingei honors utility, humility, and the quiet dignity of hand-made things. Their pieces were not displayed to be admired behind glass, but used, worn, passed down—objects that held both function and soul. At the museum, you’ll find that beauty doesn’t shout; it lives in the familiar grain of wood, the curve of a handmade bowl, the balance of weight and use. It is a space that invites you not just to look, but to feel—to recognize that care, not acclaim, is what gives an object life.

That belief still echoes across Japan today. In unassuming workshops and regional studios, craftspeople continue to uphold techniques passed down for centuries—not for preservation’s sake, but because these ways of making still serve. And still move us.

Woodwork and woodblock carving: Tools that honor the grain

In Japan, the way wood is worked speaks to a long-standing relationship with nature—quiet, respectful, and deeply attuned. Whether it’s the delicate art of woodblock carving or the structural ingenuity of joinery, wood has never been just material. It’s a living presence—something to be read, listened to, and shaped with humility.

Take hanga, or traditional woodblock printing. Rooted in the Edo period, it gave rise to iconic ukiyo-e prints that captured fleeting beauty and everyday life. These works began not with ink, but with wood—carefully carved cherrywood blocks, each etched by hand to mirror the original brushstroke. It’s a practice that balances skill and intuition, where the carving itself becomes part of the art.

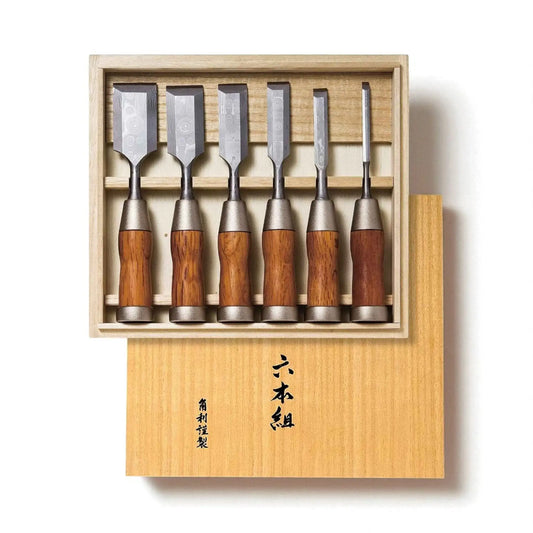

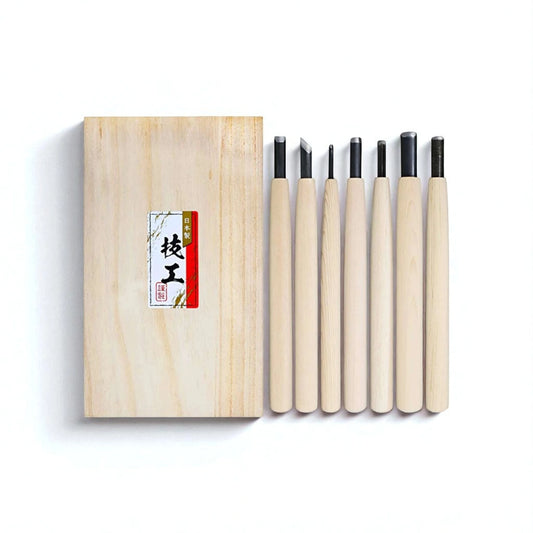

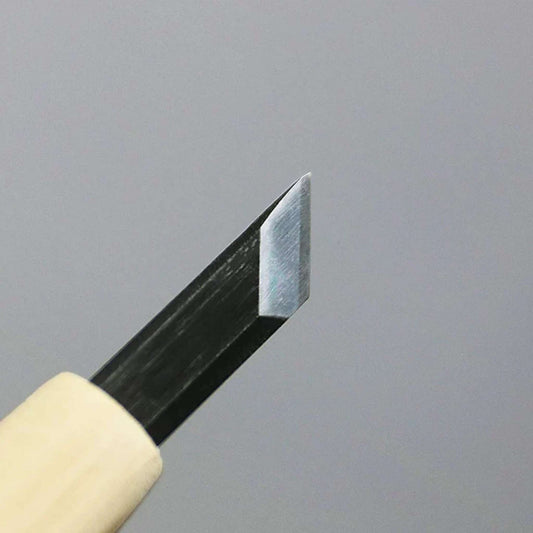

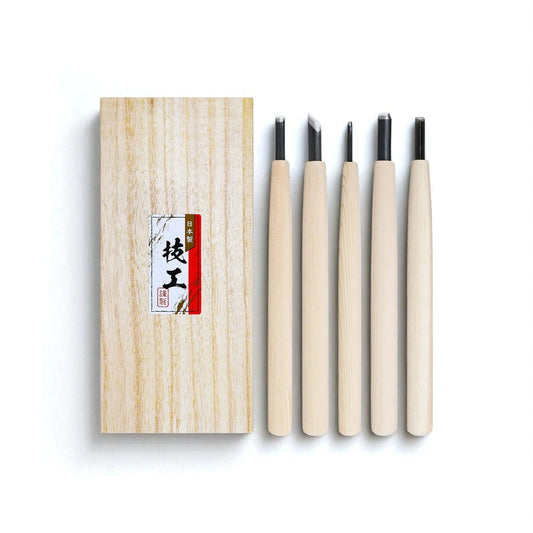

The Kakuri Hand-Forged Tsuchime Aogami Wood Carving Knife Set (10 pcs) echoes this sprit. Designed for control and sharpness, each blade allows the user to work with the grain, not against it. Whether recreating traditional prints or carving original designs, the process encourages a slower rhythm and a more tactile sense of creativity.

Woodworking in Japan, by contrast, is often structural—but no less poetic. It is a discipline that privileges silence, alignment, and patience. Traditional joinery methods—like kumiko and sashimono—require no nails or adhesives. Instead, they rely on precisely interlocking components shaped by chisels and saws, designed to breathe with the seasons. These structures do not resist time; they live alongside it.

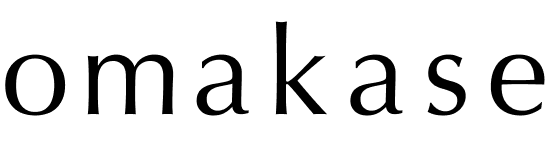

The Kakuri Japanese Damascus Chisel Set (6 pcs) pays tribute to this philosophy. With layered steel and precision balance, these chisels enable work that is guided as much by feel as by form. Used in temple architecture, cabinetry, and furniture-making, these tools reflect a discipline where nothing is hurried and nothing is hidden. Even for beginners, their heft invites reverence, connecting hand to heritage with every careful cut.

Both woodblock carving and joinery arise from a shared sensibility—one that values listening, not just cutting. The act of making becomes a quiet conversation with the tree, the tool, and the craftspeople who shaped before us.

Kintsugi: A repair that reveals

In Japanese culture, things are not discarded simply because they are damaged. To mend is not just to fix—it is to honor. Kintsugi, the centuries-old art of golden repair, embodies this belief. Rather than hiding cracks, it illuminates them. The fracture becomes the focal point. The mended object becomes more precious for having been broken.

Kintsugi has roots in urushi lacquer repair, a technique used to restore broken ceramics with sap harvested from the lacquer tree. When dusted with gold powder, the repair takes on a luminous thread—a mark of survival, not flaw. At the heart of this practice is mujō, the awareness of impermanence. To see a cracked bowl not as ruined but as changed.

Our Kintsugi Starter Kit offers an introduction to this philosophy. Using food-safe materials that reflect traditional methods, the kit invites a different mindset. It’s not about perfection—it’s about attention. The moment you begin to mix the repair paste, something shifts. The broken becomes less daunting. And the act of mending becomes a kind of dialogue—with the object, with time, and with your own habits of care.

Many who try kintsugi for the first time say the process feels unexpectedly emotional. It asks for presence. It reveals how we relate to damage—not just in things, but in ourselves.

Washi papermaking: The art of holding light

Washi, Japan’s handmade paper, is a paradox. It is feather-light yeta incredibly strong. Translucent, yet full of texture. For over a thousand years, washi has been used for everything from shoji screens and calligraphy scrolls to currency and sacred texts. And yet, its origins remain profoundly simple: water, fiber, motion.

The process begins with kozo, the inner bark of the paper mulberry tree. After steaming, stripping, and beating the fibers, they’re suspended in cold water with neri, a mucilaginous extract from the tororo-aoi plant. This ingredient ensures an even suspension, allowing the fibers to float and bond as the papermaker lifts each sheet with a sugeta screen. No two sheets are ever quite the same.

To witness this process—whether in the snowy basins of Echizen or in a hillside studio in Tokushima—is to witness patience in motion. There are no shortcuts. No machines that can truly replicate the subtle, uneven, living quality of washi.

The Japanese Washi Paper Crafting Kit offers a rare opportunity to step into this rhythm. With hand-processed kozo pulp and the essential tools, you can experience the physical and emotional quiet of papermaking. As the water drains, the fiber settles—and in that moment, the paper holds more than pulp. It holds the pace of your hands. The room’s stillness. The season’s breath.

Washi isn’t a medium. It’s a trace of how something was made.

To engage with Japanese craft is not to learn a technique. It is to enter into a relationship—with material, with time, and with the invisible lineage of those who came before.

A respect for texture. An awareness of impermanence. A belief that beauty is not added at the end, but cultivated from the beginning.

These are not just tools and kits. They are invitations—to look closer, work slower, and discover something enduring in the simplest acts of making.

Explore our curated selection of Japanese tools and crafting kits.